I Hope You’re Wrong: Why Being Right Can Be More Dangerous Than Being Wrong

One of the persistent temptations in investing is the belief that the future can be known, rather than simply estimated or viewed through a lens of probability.

Every so often, markets appear to reinforce this belief. It can happen when an analyst makes a sweeping economic call, a television personality highlights a stock, or an investor acts on a strong conviction about a single event. When such a call lands correctly, an investor’s confidence tends to grow much faster than their actual wisdom. This creates a unique brand of risk where the danger isn't being wrong but rather being "right" in a way that encourages all the wrong lessons.

Experience has taught me to treat these moments with caution, as a successful forecast can lead to increased activity, narrower positioning, and a reduced tolerance for uncertainty.

The pull of prediction

We currently live in an environment where market commentary often comes with an air of certainty. Forecasts with clean narratives and specific numbers can create the impression that the future is more orderly and manageable than it actually is. In this context, investing can begin to resemble wagering on specific outcomes rather than planning for inherent unpredictability.

The reality is that markets are complex adaptive systems shaped by a mix of fundamentals, incentives, psychology, policy decisions, and randomness.

Consequently, when a prediction proves accurate, it is rarely clear whether the result stemmed from genuine insight or mere circumstance. Because markets largely reward outcomes without distinguishing between skill and luck, investors are often left to conclude that their success was due to brilliance rather than chance.

Famous calls and their aftermath

History is generous in celebrating bold forecasts. Michael Burry, for instance, is rightly remembered for identifying the housing market excesses before the Global Financial Crisis. It was a significant call that required immense conviction and a high tolerance for sustained discomfort. However, what receives less attention is what happens after such a call is made. Since that episode, Burry has repeatedly warned of impending market downturns; while some concerns were thoughtful, many were premature, and others have been incorrect.

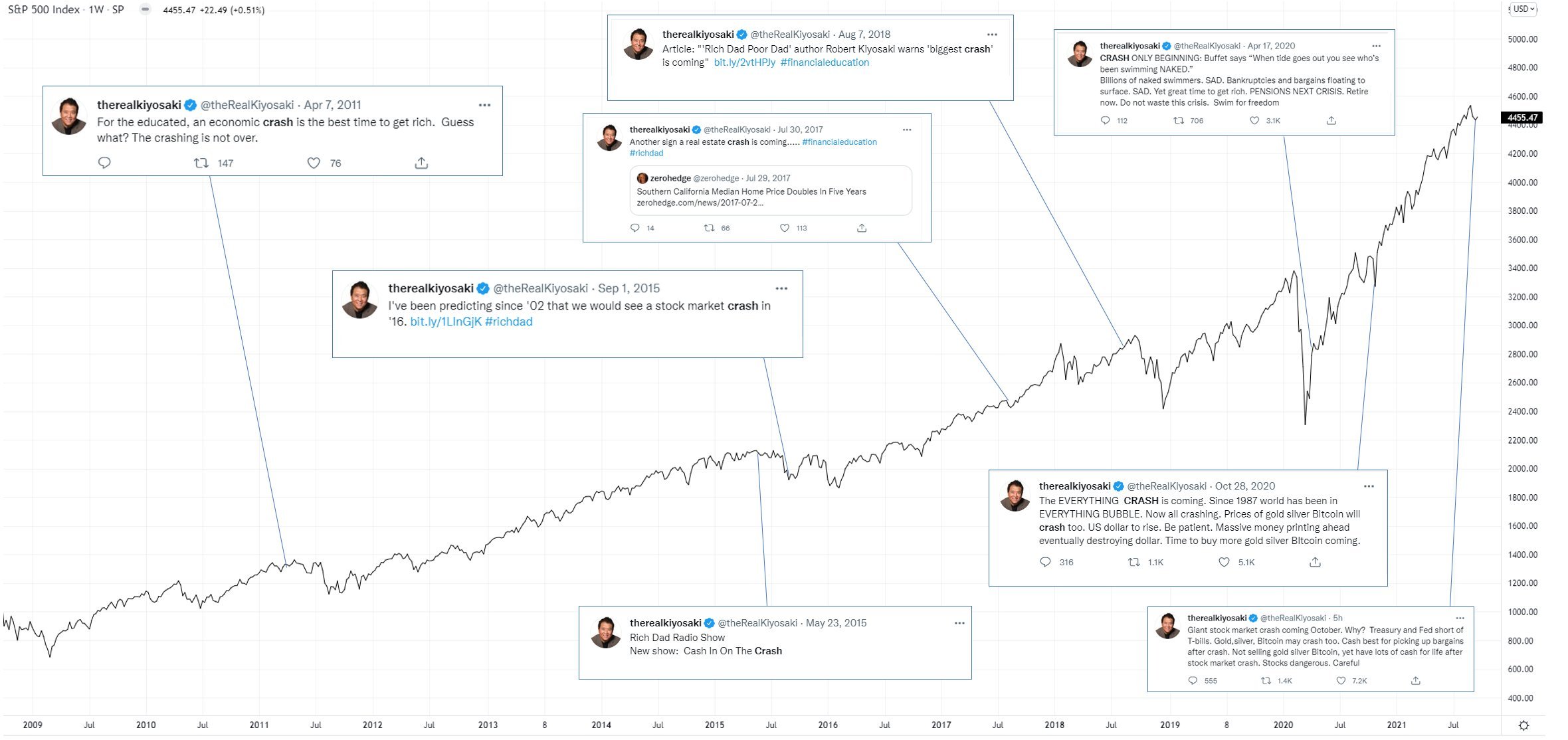

We see a similar dynamic in the warnings issued by public figures. Robert Kiyosaki, for example, has repeatedly forecasted systemic collapse. The chart aligns several of those warnings with the path of the S&P 500, which over that period moved materially higher.

With enough attempts, even low-probability calls will eventually intersect with actual outcomes.

The common thread in both examples is that forecasting is rarely a single bet. One successful prediction often creates pressure to make another, or to double down on a view even after the market has moved on. This pattern reveals a fundamental distinction for investors: the difference between trying to be "right" and actually making a prudent decision.

The danger of fixating on outcomes

That difference becomes unavoidable when we examine how outcomes are derived.

As professional poker player and author Annie Duke has observed “We are too quick to treat outcomes as a referendum on decision quality, when luck plays a much larger role than we are comfortable admitting.” This insight sits at the core of disciplined investing.

Outcomes, on their own, are an unreliable measure of decision-making. Well-reasoned decisions can lead to disappointing results. Poorly reasoned decisions can occasionally be rewarded. Over short periods of time, randomness can obscure the underlying quality of the process.

The challenge is that investors are wired to equate results with decision quality. If we judge our strategy solely by whether it was correct in the short term, we reinforce behaviors like excessive conviction and a refusal to reassess our positions. A more durable standard is required, one where the most important question is not whether a view proved correct, but whether the plan was robust enough to withstand being wrong.

The high cost of being too certain

When outcomes are mistaken for skill, the resulting overconfidence can quickly become destructive. Investors who believe they can forecast the market often increase their trading activity, bet too heavily on one specific direction, and abandon the protection of diversification in favor of short-term signals.

The irony is that the more certain an investor becomes, the more fragile their strategy tends to be. Portfolios built on specific predictions only work if those predictions come true, which provides a dangerously narrow margin of safety.

A different standard

From a fiduciary perspective, the objective is not to anticipate each market event correctly. It’s to build resilient plans that remain viable across a wide range of outcomes. This requires accepting uncertainty as a permanent feature of the landscape and prioritizing asset allocation, tax awareness, and emotional resilience over the allure of the next big forecast. While a prediction may be correct, any approach that depends on it’s success is fundamentally fragile.

Why I hope you’re wrong

Ultimately, when I hear a confident market prediction, my internal response is often, “I hope you’re wrong.”

My reaction is not born out of cynicism or a desire to see someone fail. Rather, it reflects an awareness of how slippery the slope can be once a prediction proves correct. Being wrong, while uncomfortable, serves an important purpose of reinforcing humility and preserving discipline.

Markets have a long history of humbling those who claim certainty. The investors who truly succeed over decades are those who respect that history, choosing to build financial plans that remain intact across a wide range of outcomes, including those they did not anticipate.

Disclosure: This commentary is for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment, tax, or legal advice. The views expressed are based on current market conditions and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and no investment strategy can guarantee success or protect against loss. References to specific companies are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Investors should consult with a qualified financial professional before making any investment decisions. Human Investing is an SEC-registered investment adviser. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.