Investing isn’t just about numbers. For many, it’s about making choices that reflect personal values while still aiming for long-term investment growth.

One of the more common questions we hear from both clients and prospective clients is, “How can my portfolio better reflect what I care about?” Often, that means avoiding certain industries or intentionally supporting companies with similar values, essentially “voting with your dollars” through your investments. Enter ESG investing: a way to invest while considering Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors.

Because ESG investing is relatively new and can look differently depending on the investor’s approach, let’s break down what ESG is, how it works (including common misconceptions), and whether it might make sense for you.

What ESG Investments are (and are not)

ESG investing considers how companies operate beyond profits. ESG is a metric that measures impact in the following areas:

Environmental: How a company navigates environmental issues like climate impact and sustainability practices

Social: How a company supports and interacts with the people and communities it impacts, from its workforce to suppliers to local communities

Governance: How it’s run through board diversity, executive pay, and transparency

Although ESG is designed to align investments with values, ESG is not charity. These portfolios still aim for returns and ESG ratings vary widely, so it should not be assumed every “ESG” fund is equal.

How did ESG Investing begin?

Although popular ESG index funds (such as ESGV and VFTAX) were launched just in the last 10 years, the intention of aligning money with values has been present for centuries.

As early as the 1700s, religious groups such as the Quakers practiced forms of values based investing by avoiding businesses involved in activities they believed caused harm, including weapons, slavery, and exploitative labor. These early decisions reflected a belief that how money is earned matters.

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) gained traction in the 1960s and 1970s with the anti-war movement, as investors sought to divest from companies connected to the Vietnam War and apartheid in South Africa.

The early 2000s were marked by a desire from investors to have more structured ways to evaluate non-financial risks that could impact long-term performance.

In 2004, the United Nations published the report Who Cares Wins, formally introducing the term ESG to describe factors such as environmental impact, labor practices, and corporate oversight.

Today, ESG is widely used by both individual and institutional investors. However, because ESG developed across multiple frameworks over time, its ratings and methodologies are not standardized.

How does ESG Investing work?

ESG investing can take several forms:

Screening: Excluding companies that don’t meet certain standards (e.g., defense contracts, tobacco, weapons, fossil fuels, alcohol, gambling).

Positive selection: Choosing companies that actively perform well on ESG metrics such as greenhouse gas emissions, workforce diversity and inclusion, and human rights protections.

Shareholder advocacy: Investors upholding companies to improve their ESG practices.

What are the benefits of ESG Investing?

Values alignment: You invest in companies that reflect what matters to you.

Long-term risk management: Companies with strong ESG practices may be better prepared for future regulations or reputational risks.

Growing demand: ESG investing is becoming more mainstream, with more selections and better data.

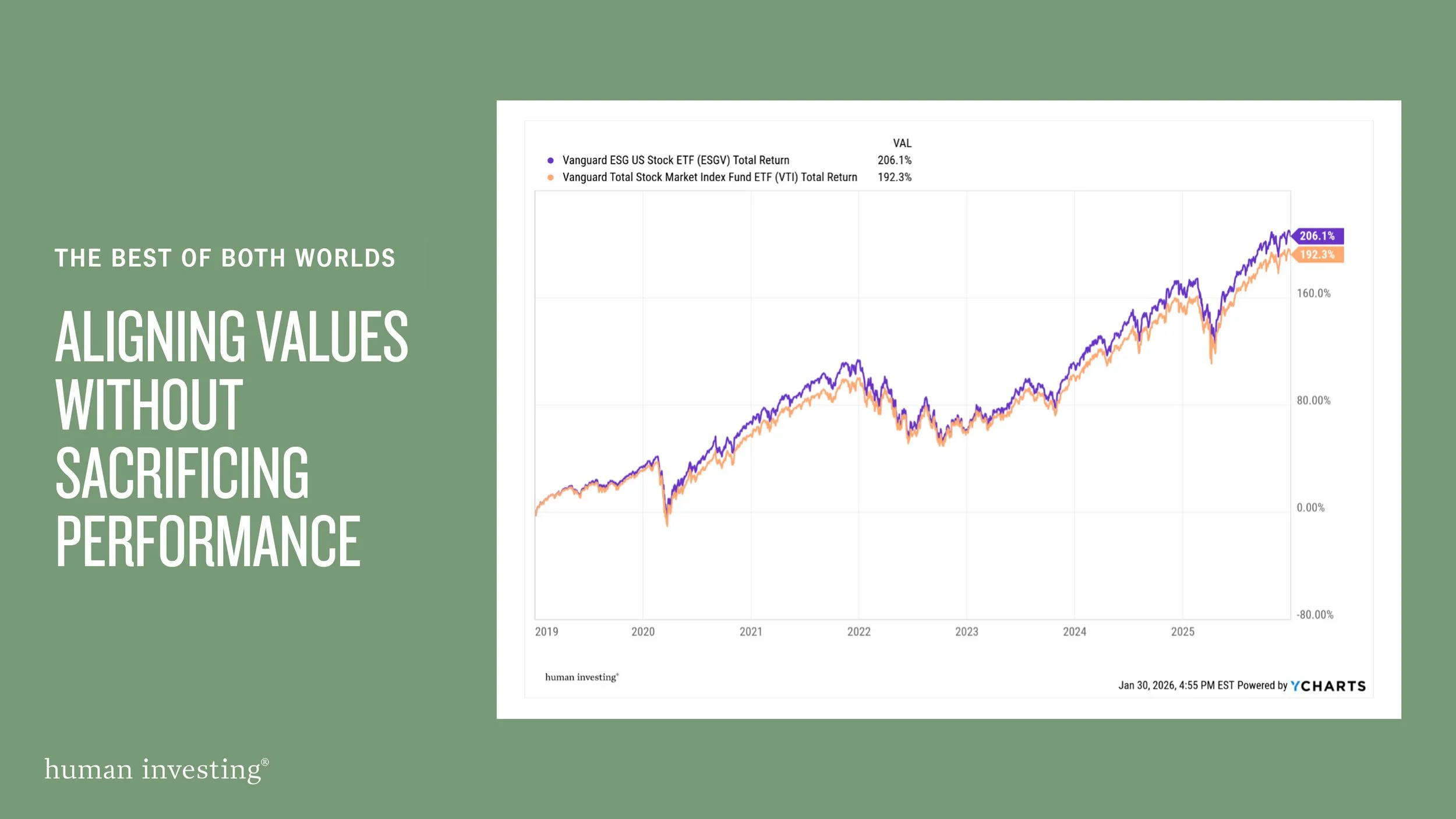

Competitive returns: Although long-term data is still developing, several established ESG funds have delivered returns comparable to traditional index funds over the past 5–9 years.

Data courtesy of YCharts. From 1/1/2019 to 12/31/2025, Vanguard ESG US Stock ETF (ESGV) delivered similar returns to Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF (VTI), while also experiencing higher volatility due to a heavier tech concentration. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Navigating the trade-offs in ESG investing

While ESG investments can improve alignment with your values, it is not a comprehensive or perfect solution. Some companies you think should be screened may not.

For example, Walmart may still be an investment despite their firearms and tobacco sales, as they derive the majority of their profit from groceries and home goods.

Additionally, Tesla may also be included as an investment in an ESG portfolio due to its sustainable energy focus, despite the controversy around some senior leadership of the company.

Here are some other considerations and common misconceptions with ESG investments:

Inconsistent ratings: ESG scores aren’t standardized, so one company might be rated differently by different agencies.

Limited diversification: ESG funds may exclude certain sectors, which can make the resultant investment less diverse.

Greenwashing: Some companies may appear ESG-friendly without meaningful action.

Higher fees: ESG funds can sometimes carry slightly higher expense ratios.

Five essentials for your ESG strategy

Define your values: What issues matter most to you – climate change, human rights, corporate ethics, etc.?

Explore ESG funds: Look for mutual funds or ETFs with ESG or SRI (Socially Responsible Investing) labels.

Check your current investments: You may already be invested in funds with ESG screens.

Talk to an advisor: A financial advisor can help you align your portfolio with your values.

Start small: You don’t have to overhaul everything. Try allocating a portion of your portfolio to ESG choices.

Final thoughts

Although ESG portfolios offer a way of value-driven investing, every portfolio has its limitations. With the right approach, you can align your money with your values, while still aiming for financial success.

Want help exploring ESG investments in your portfolio? Let’s talk!

Disclosure:This content is for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended as investment, legal, or tax advice. The strategies and steps outlined—such as building an emergency fund, contributing to employer-sponsored plans, paying down debt, or using HSAs, IRAs, and taxable accounts—are general in nature and may not be appropriate for every individual. You should consult a qualified financial or tax professional before making decisions based on your personal circumstances. There is no guarantee that following any financial strategy will achieve your goals or protect against loss. References to interest rates, contribution limits, or tax rules reflect information available at the time of publication and may change. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Advisory services are offered through Human Investing, an SEC-registered investment adviser.