We talk to a lot of different people about investing. A common request is something along the lines of: “I don’t want to lose anything, and I want my money to grow.” This is a challenging, if not impossible mission. The investment world is full of opportunities to grow your money. However, there is an inherent risk when you put your money in any investment.

Finance has a lot of ways of measuring risk. Standard deviation is used to try to show a range of the possible returns. Max drawdown displays your worst-case scenario. Sharpe ratio provides a risk-adjusted measure of performance. However, very few investors ask about standard deviation, max drawdown, and Sharpe ratios. The people we talk to are most likely to ask “What are the odds of losing money” because they don’t want to see their current savings drop in value.

How strong is your purchasing power?

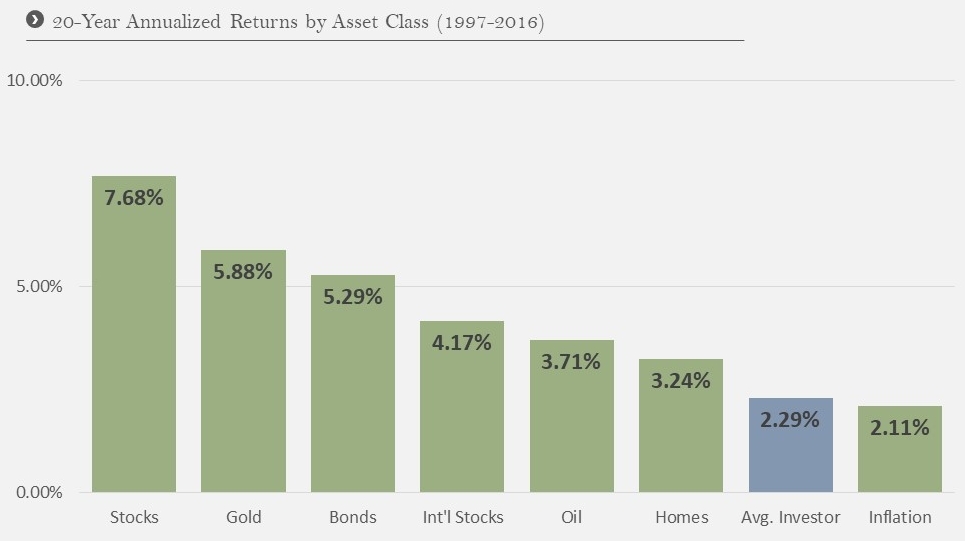

An important consideration when talking about losing money is purchasing power: the ability to buy goods with your money. Inflation has consistently pushed prices up over time, reducing the purchasing power of a single dollar. Wanting to avoid losing money is completely understandable. The danger of keeping your money under your mattress or sitting in cash is that inflation is constantly reducing your purchasing power.

When concerned with losing money, many investors are focused on nominal returns. Nominal returns are the raw return values, unadjusted for inflation, and are simple to calculate and digest. I would argue that most investors should be focused on real returns: returns adjusted for inflation. Real returns are a more accurate measure of your change in purchasing power. Ultimately, very few outside of Scrooge McDuck want a giant pile of money. Most people want to spend that money on goods, like food, travel, or a home, therefore purchasing power is likely what investors really care about.

Real return = (1+Nominal Return) ÷ (1+inflation rate)

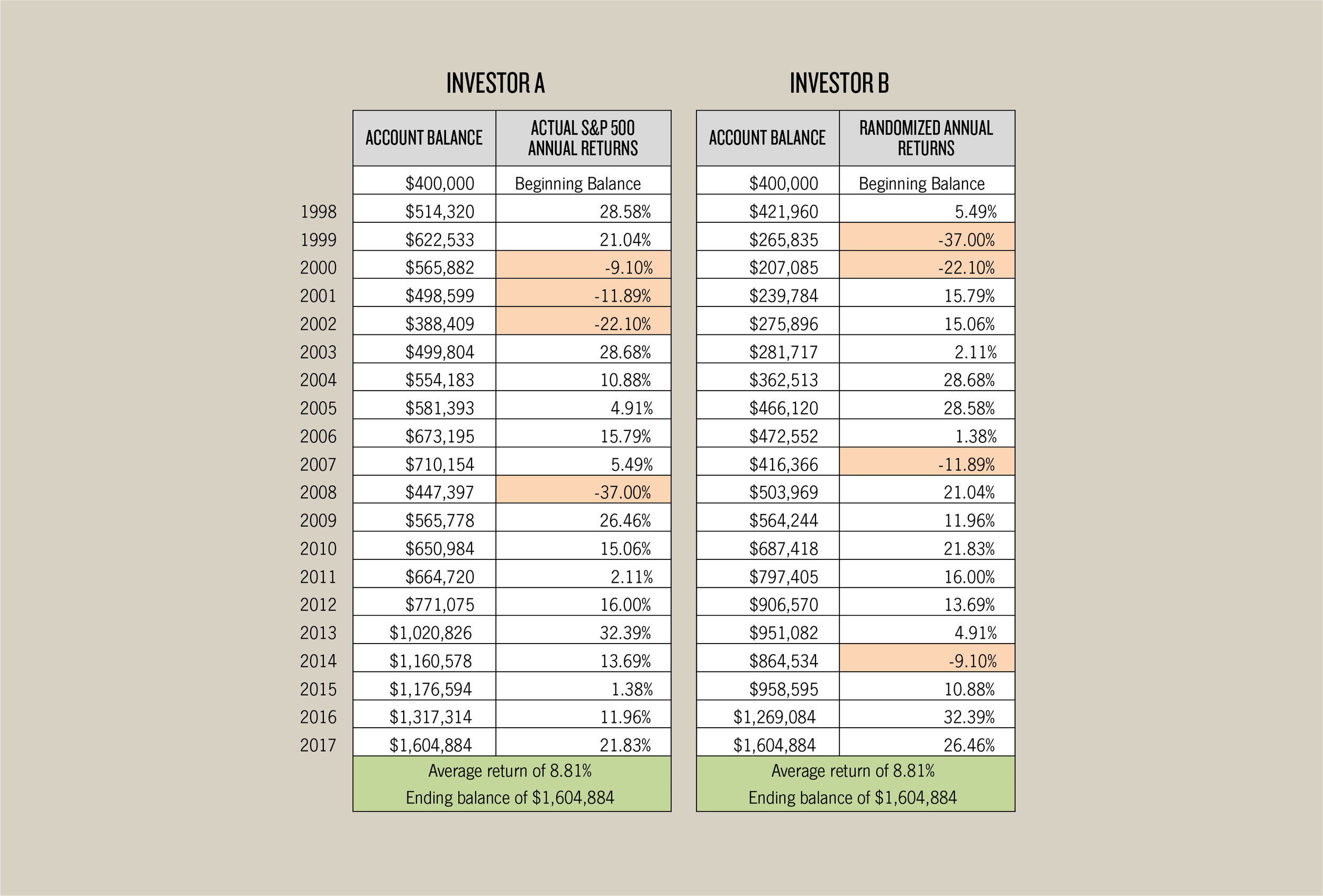

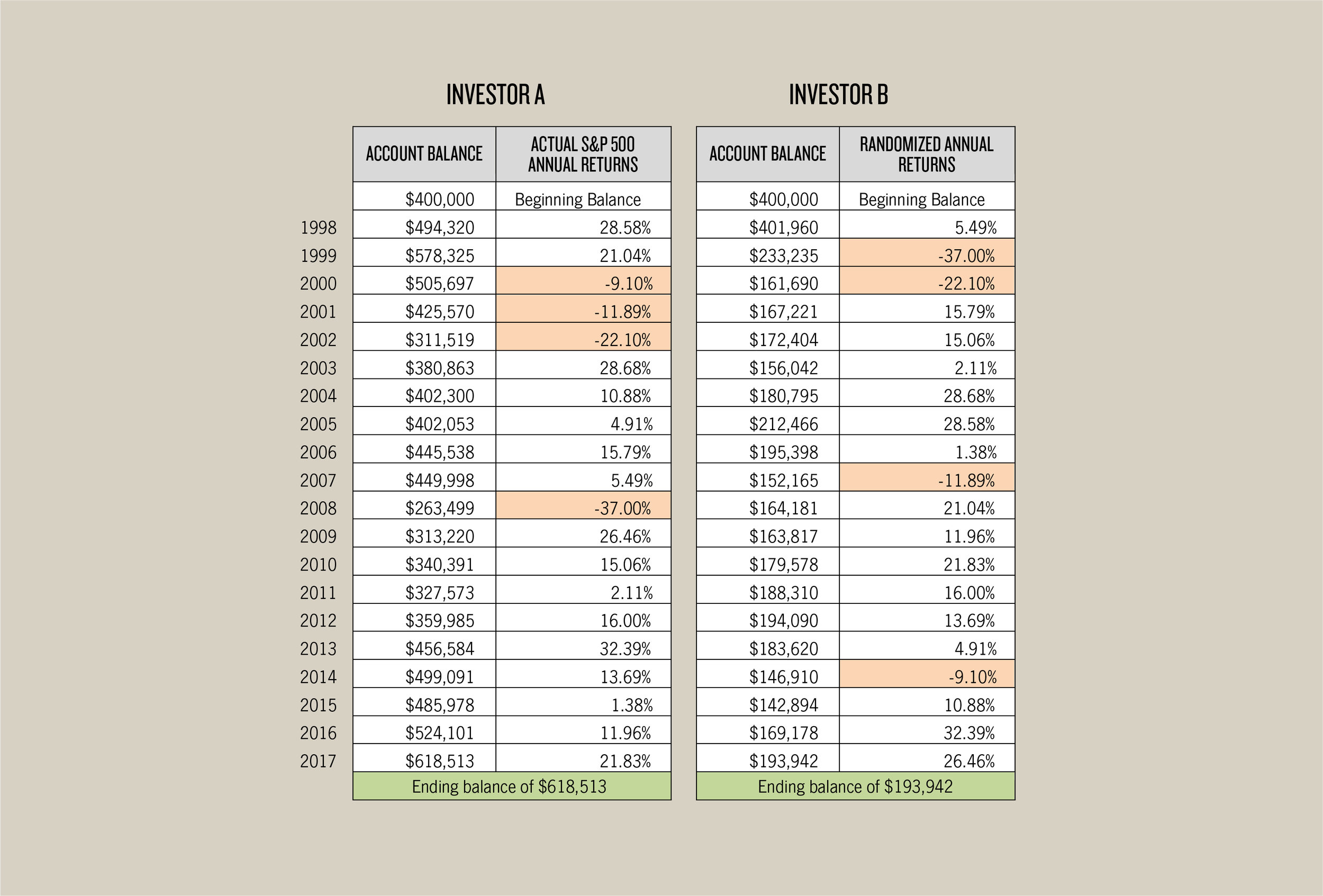

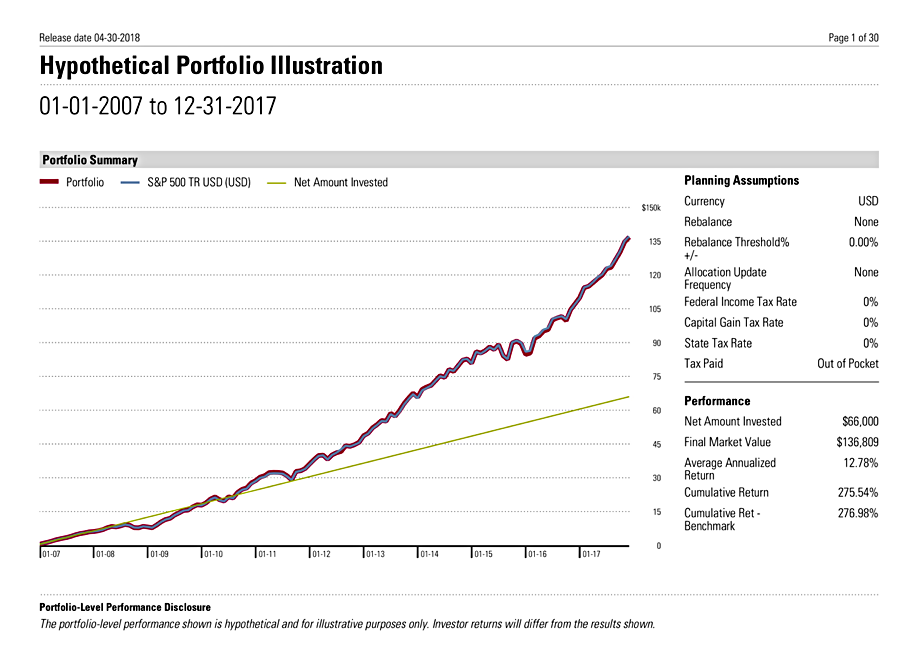

Historically, stocks deliver positive returns, and those returns are in your favor. However, stocks are down (i.e. lose money) more frequently than bonds. The safety bonds offer also means they provide lower returns. What blend of stocks and bonds is most likely to protect your purchasing power (i.e. produce a positive real return)?

inflation is dwindling BOND power

To try and answer this question, I looked at the Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation (SBBI) data from the CFA Institute from 1926-2020. This data included monthly and annual returns; the annual data is for each calendar year. For stocks, I used the Ibbotson SBBI US Large-Cap Stocks total return.

For Bonds, I used the Ibbotson US intermediate-term (5 year) Government Bonds total return. I looked at several different portfolios which include a variety of stocks and bonds. Specifically, I blended the stocks and bonds in 10% increments, from 100% stocks, to 90% stocks 10% bonds, to 80% stocks 20% bonds, and so on to 0% stocks 100% bonds. I also assumed the portfolios were rebalanced at the start of each return period (i.e. the weights were reset at the start of each month for monthly data, and the start of each calendar year for annual data).

I took these different stock/bond portfolio mixes, and I calculated the nominal and real returns from 1926-2020 for both monthly and annual (calendar year) returns. I then calculated what percentage of returns were positive to measure the chance of losing money (nominal returns) or purchasing power (real returns). I’ve graphed the nominal vs real returns for monthly and annual returns below.

You’ll notice the nominal monthly returns paint a clear picture. If you want positive nominal returns more often, you want to own more bonds, hence the steady upward trend to the graph. If you look at the annual nominal returns and want to maximize your chances of a positive nominal return, you actually want a 10/90 portfolio (10% stocks, 90% bonds). As risky as stocks seem, having at least a sliver of stocks actually increases the chances of a positive nominal return

The real returns tell a slightly different story. For the monthly real returns, the stock/bond mix is almost irrelevant for producing a positive return, and hovers right around 60%. There is a drop off after 10/90 (10% stocks, 90% bonds), indicating owning even just 10% stocks in your portfolio helps increase your chances of positive real returns better than owning 100% bonds.

For the annual real returns, you can see that your odds of a positive real return are better with at least some bonds in the portfolio. Interestingly, the 70/30 portfolio and the 20/80 portfolios produce the highest chance of a positive real return. The all bond portfolio, 0/100, has the worst chance of maintaining your purchasing power (i.e. producing a positive real return).

Stocks can seem risky, and the loss of value can make many investors shy away. Even just a small amount of stocks can protect your purchasing power better than owning only bonds. There are still many considerations for how you should invest including your risk tolerance, time horizon, and holistic financial plan. If you’re interested in talking to an advisor, please reach out to us at hi@humaninvesting.com or 503-905-3100.